Abstract

This essay will present basic historical information about the Royal Game of Ur and several iterations of this game in a games workshop during the “Critical Game Studies” class of the “Computer Games Design” course at University Campus Suffolk. The iterations will be discussed upon and at the end a new set of rules will be agreed upon for this ancient game. The terms “Mechanics”, “Dynamics” and “Aesthetics” refer to the work of Hunicke et. al, “MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research” and will be used as such. In their work, “Mechanics” refers to the state of the game before the actual play session, including all the game bits and rules of the game, “Dynamics” refers to the emergent player behavior during the actual play sessions, while “Aesthetics” translates into the emotions that the players are experiencing as a direct result of playing the game.

Introduction

The Royal Game of Ur is an ancient game that was initially found in the excavations of the royal tombs of the city of Ur by Sir Leonard Wooley between 1926-1930. The original game tablets found date from 2600 BC and for some time after their discovery no exact rules were known. After a series of fortunate events (Finkel, p. 16, 2008) the rules of an iteration of the Royal Game of Ur were found and translated from clay tablets stored in the British Museum archive by historian Irvin Finkel. These, however, are not necessarily the original rules of the game. It is still argued whether or not the original Game of Ur was, in fact, a divination ritual practiced by priests (Becker, p. 13, 2008), but this is not the subject of this essay. There are 2 known versions of the game board used for the Royal Game of Ur, both of which have 20 squares, and, as such, I will refer to this game as “The Game of 20 squares” from now on.

Play testing and iterative process

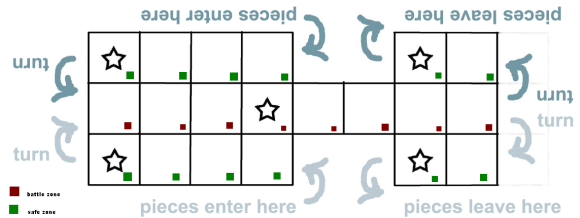

The first game board is the original one found in Ur by Wooley and has 2 “safe zones” for each player, while in the second and more recent one (and also the one which corresponds with Finkel’s found rules), the second safe zone for each player has been placed in the middle section of the board, creating a longer section in which the players can “battle”.

The first step in iterating this game was playtesting it several times. After a few games, it was decided that the second board suits the purpose of creating a more competitive game better, and was elected to be the board on which the iterations will take place.

The playtest rules, as found in Irving Finkel’s book (Finkel, 2005), are as follows:

- each player starts with 7 token

- each player starts on opposite sides of the play board

- players decide which of them starts first, on arbitrary methods

- the player who starts rolls 4 d4 dice, each tipped on 2 tips with a distinctive method (i.e. 2 of the tips are coated with Tipex, 2 are not)

- the player moves a single token as many squares as tipped dice he rolled. If he rolled no tipped dice, then he loses his turn

- if a player’s token lands on a “rosette” square (marked with stars in above illustration), he gets another turn

- the purpose of each player is to get all his tokens out of the board, following the movement in the above illustrations

- if a player’s token should move on top of another player’s token as a result of a dice throw, then the player whose token was on the square first loses that token and has to start it into play again. This move is referred to as “capturing”

- a token on a “rosette” square is considered “safe” and cannot be “captured”

- if a player has no “legal” moves on his turn, he loses that turn

With those in mind and our chosen game board, my play test partner and I started playtesting this game. My first thoughts on the game were that the iterations made to it should serve its original purpose more, that of (maybe) divining the future. Reading through Andrea Becker’s essay, I noticed that there existed a variety of game boards. This idea was solidified by Finkel, who stated that “Boards for the Game of Twenty Squares become increasingly common throughout the second and first millennia BC and over one hundred examples are now known from Iraq, Iran, Israel, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Cyprus, Egypt and Crete”. As with the Stenway game, which was supposedly played by a priest with the warchief of his village before a war, or Alea Evangelis which was played as a metaphor of Jesus’s pilgrimage through Jerusalem, I imagined that this game could be played by players from a variety of social backgrounds, a fact solidified by Becker’s observations of the different game boards that have been found in Wooley’s excavations. To better view the game’s original purpose, I mentally planned some scenarios around which iterations were created.

The first scenario was that of the warchief playing to determine an upcoming battle’s result, or that of a royal child playing in order to learn more about tactics. To illustrate this, my partner and I assumed the mantle of a priest and a warchief preparing for battle. In this case, luck did indeed play a very important role, but, more importantly, the player’s mind must be sharp and must not let itself be cornered, or trapped. Thus, the first iteration arrived: in stead of Finkel’s “if a player has no “legal” moves on his turn, he loses that turn”, we transformed it into “if a player has no “legal” moves on his turn, he loses the game”, for, as a warleader, you must always have an escape plan, or be one step in front of your enemy. As a great tactician, this remains true.

The second scenario was that of the warriors challenging each other to a game of 20 squares. What would they want? Within the guises of ancient Ur-ian warriors, it was decided that they would want to see which warrior has the most battle prowess, by noting how many foes would each down (Tolkien, p. 555-565, 1954). To increase the chances of each warrior, us, as game designers, decided to go for “the frag system”, also adding a “skill frag”. As such, each successful “capture” counted as a “frag”, and a piece captured between two pieces of the opponent’s would count as a “skill frag”, adding 2 “frags”. The game would end after 20 turns of each player’s and the winner would be the one with the most “frags”. To add to the actual mechanics of the game, if a player managed to get a piece off the board, he would get 2 “frags” and get to roll again, the token that went out being put back into play.

The third and last scenario was that of prisoners playing the game as an activity to pass time in prison. As such, we thought of an iteration that would incorporate the everyday reality of their life into the game and we came up with the idea of using a “cell” in which the “captured” pieces would go, and the player would only be able to put them back into play by throwing a 2 when his turn came.

These iterations were made to the game to add to the veracity and the feel of the game and how it was supposedly played in the ancient times. The challenge in creating the iteration was the immensity of options with a game this old. The first challenge was choosing the board on which we would play the game. Should we chose the original one of the 2nd century BC one? After that decision was made, the iterative process kicked in, which resulted the above iterations which were made not only to add to the replay-ability of the game, but also sought to bring to front some of the scenarios in which the game could have been played in the ancient period.

Regarding the iterations and purely the game design part of them, the first and last iterations do not add to the dynamics (Hunicke et. al, 2004) of the game very much, the only changes that have been noticed in the gameplay being that in the first iteration of the game there were almost all the pieces in the game from the 7th or 8th turn of each player, and each sought to block the other player rather than try to get the pieces out of the board, as originally intended. The challenge with the 3rd iteration was getting the number that needed to be rolled just right. Initially, it was thought that 4 would be the correct one, since it was rarer, but after a few sessions of playtesting it was obvious that 4 was very rare and it would ruin the flow of the game, so we decided on the number that was the most likely to appear, 2. The second iteration was maybe the most interesting, because it changed the dynamics drastically, since the goal was to have the most “frags” after 20 turns of play, which meant that the players would try and find the best way to move their pieces so they would either get normal “frags” or “skill shots”. Also, it bears noting that “strong points” were established in each game on the middle “rosette” squares, by having the first player that landed on them not surrendering them until they weren’t sure of having a better tactical advantage.

Conclusion

To conclude, the three iterations that I have made to “The Royal Game of Ur” along with my game partner have either improved the aesthetics of the game by adding an extra layer of complexity to the game or have changed the game drastically, causing a mutation of the dynamics of the game. All the other rules of the game have remained the same throughout the game sessions unless stated otherwise and the final game can be played with either one of the iterations presented in this essay, mixing and matching after your preference.

Bibliography:

Becker, A. (2008) “The Royal Game of Ur” in Finkel, ed. pp. 11-15.

Finkel, I. L. (2008) “On the Rules for The Royal Game of Ur” in Finkel, ed. pp. 16-32.

The text offers some interesting discussion of how an ancient game might be rebalanced using ideas from contemporary games design. Two of the items in the bibliography are from “Finkel, ed” but “Finkel ed” itself is missing …

I really enjoyed this Chris. What i liked most was the fact that you put yourself in the position of asking ‘what would a game like this be like if…’ I think it is really important that experimentation should be purposeful. Good work.